The Truth Never Found

By Kelly Gilmore and Jessica Tucciarone

When Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore were murdered in 1951, being African American often meant White law enforcement officers and prosecutors were less than diligent in pursuing justice on your behalf.

Seventy years after their house was bombed and they lost their lives, the Moores’ heinous murder has never been completely solved.

According to federal Department of Justice records, five separate criminal investigations into the murders – ranging from the federal to local level and from 1952 to 2008 – failed to result in any arrests, prosecutions or convictions.

“Again, remember we were in the South,’’ said William Gary, the president of the Moore Memorial Museum and Park in Mims, situated on the property where the Moores lived and were killed. “This was a state that on the surface seemed to be open and welcoming, but in reality it was probably one of the worst places for African American people to be during the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s.’’

Indeed, Florida ranked sixth in the nation in the number of lynchings of Black people from 1882 to 1968 with 257, according to data compiled by the NAACP.

When the Moores were killed in 1951, it was common in many Florida communities for local law enforcement officers to also be members of the Ku Klux Klan, according to federal Department of Justice records. With such a skewed justice system, the investigator’s path to solving the Moores’ case was bleak at best.

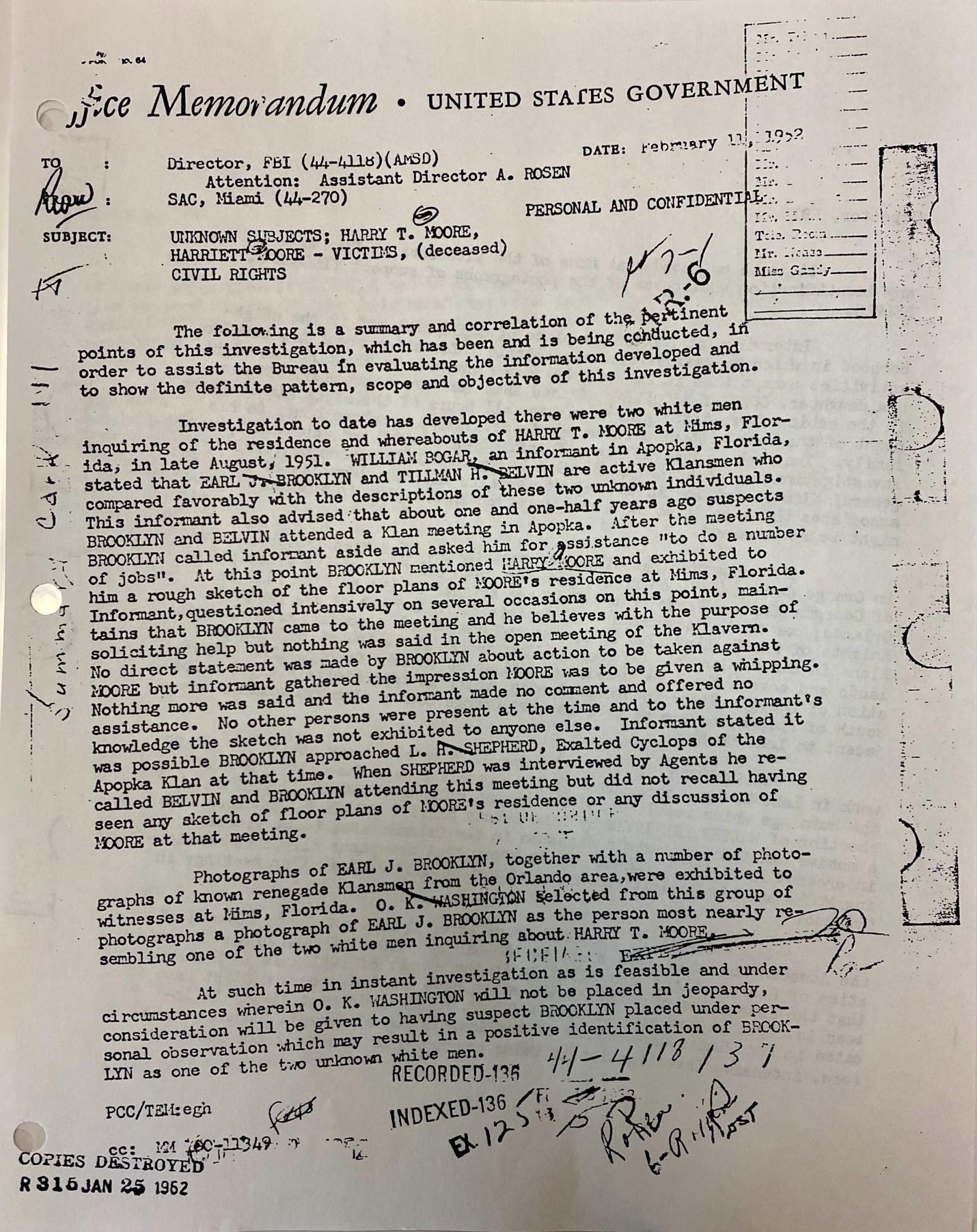

Prompted by national newspaper headlines decrying the Moores’ death, the FBI launched an extensive investigation in 1952. According to Department of Justice records, FBI investigators discovered that Harry Moore’s civil rights activism made him a known target of the Klan. Agents questioned three Klan members, one of whom, Joseph Cox, committed suicide the day after being interviewed by investigators. Evidence also pointed to Earl J. Brooklyn, a Klansman with a violent reputation who reportedly was in possession of floor plans of the Moore home and recruiting volunteers to assist in the bombing. However, nobody was arrested in the case.

“They interviewed various people, according to what I have read, who confessed to having a part in that, but I believe they were discounted because the stories didn’t hold up,” Gary said.

The FBI did not pursue the case further.

“In other words, the officials in Washington did not want to stir up possibly prosecuting a White person for killing a Black man, particularly one who was a leader in the NAACP in the South during that time because they were afraid it might cause an uproar in the community,” Gary said.

It wasn't until 1978 that the Moore case would be reopened. This time, Brevard County Sheriff Roland Zimmerman assigned Capt. Winston J. Patterson to the case.

During this investigation, a former high-ranking member of the Ku Klux Klan in Central Florida, Edward L. Spivey, contacted the sheriff’s office on numerous occasions. Spivey was enraged with the sudden new interest in the cold case and wanted to meet with investigators. Spivey, suffering from late-stage cancer, implicated Joseph Cox in a deathbed confession, saying his friend was responsible for the bombing, according to Department of Justice records. He told investigators Cox came to his home and confessed that he had been paid by the Klan to kill the Moores. Following this private confession, Cox borrowed a shotgun and committed suicide.

Investigators suspected that Spivey was involved in the bombing because he knew so many details about it, according to Department of Justice records. But he was never charged, arrested or prosecuted and he died in 1980.

In 1991, Gov. Lawton Chiles assigned Florida Department of Law Enforcement Inspector John Doughtie to reopen the case. Doughtie followed up on possible leads and potential suspects but turned up nothing.

In 2004, then-State Attorney General Charlie Crist reopened the case again, interviewing more than 100 people and conducting an excavation of the site of the Moore’s home, according to Department of Justice records. Investigators re-interviewed many of the people originally interviewed by the FBI, as well as many other neighbors of the Moore’s not interviewed at the time of the bombing. Crist concluded that Brooklyn, Cox, Spivey and another Klansman, Tillman H. Belvin, were likely responsible for the bombing. But by that time, all four men were deceased.

“Well, I had come to the conclusion that nobody really had solved the case and come to a solid conclusion if you will, and I thought that was wrong that justice always needs to be done if it is all possible,’’ Crist said. “That's simply the reason why I reopened the case.”

One last effort was made in 2008 when the FBI reviewed the case as part of the Department of Justice’s “Cold Case Initiative” under the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007. The FBI reviewed the previous investigations and files and conducted more interviews. Investigators concluded that 10 former members of the Central Florida Ku Klux Klan knew about the bombing, but that eight of the potential witnesses were confirmed to be dead, and two were unable to be located, but suspected to be dead, according to Justice Department records.

Unfortunately, after tireless efforts to conclusively solve the case over the last 70 years, the trail went cold over time as evidence was destroyed, key witnesses were deceased, and no new evidence was brought to the table. To this day the case has never been solved but will always be remembered.

The Moores’ name and legacy continues to live on even as their killers are forgotten.